Economics for Muggles: Night light and GDP

Hard evidence that China isn't quite the success story it's made out to be

This is the first post in a series that explains economic papers to non-economists (or as I call them, muggles). Posts will discuss important or unique economic papers that I think the average person will find interesting. This post will focus on the economic paper, "How Much Should We Trust the Dictator’s GDP Growth Estimates?" by Luis Martinez. With coverage by The Economist, The Times, the Washington Post, and others, this paper has made waves over the last few months. The headline-making conclusion of the paper is that authoritarian nations aren’t growing as fast as they claim to be.

Part I: Background

Economic growth is the ultimate economic question. Why do some societies have and others have not? As the Nobel prize-winning economist Robert Lucas famously said, "Once you start thinking about growth, it's hard to think about anything else.” Many of the world's best economists devote their lives to studying economic growth: what causes it, what prevents it, and what policies will increase it. To answer any of these questions, there's a simpler question that has to be answered first: how to measure it?

The traditional metric for economic growth is GDP (gross domestic product). Basically, GDP calculates the total value of all goods and services produced in a given year. GDP has its flaws, notably dealing with leisure and environment, but overall it's a good way to judge the size of an economy. Divide total GDP by the number of individuals in a nation and you get GDP per capita, which provides a good metric of a country's wealth.

Of course, someone has to calculate the GDP for each country. Most nations, poor and rich, small and large, have a government agency that does this at least once a year. In the United States, it's the Bureau of Economic Analysis, which is housed in the Department of Commerce. Economists use GDP, and especially GDP growth, as a way to track the economic health of nations around the world. Some countries, like South Korea, have been declared "growth miracles" because of their rapid GDP growth over the last 70 years. Over that relatively short time span, South Korea has grown from a developing nation to a country wealthier than Italy. Other countries, like Argentina, are often called "growth disasters" because their economies have stagnated for decades.

At any rate, governments have a strong incentive to keep economic growth positive. Whether a democracy or dictatorship, positive economic growth means a happy citizenry, which means more power for the people in charge. Negative economic growth results in lost elections, protests, riots, and coups. So it is in the government's interest to have as much economic growth as possible. This also means they have a strong incentive to lie.

It is well-known that economic numbers should be taken with a grain of salt in many developing authoritarian economies. One of the worst offenders is China. Chinese Communist Party officials are under a lot of pressure to deliver. If you want to be promoted up the ranks, your district has to show consistent economic growth. The result is, unsurprisingly, that China has consistently reported growth numbers that strain belief. Over the years it has become so blatant that Ning Jizhe, the director of the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, wrote, "Currently, some local statistics are falsified, and fraud and deception happen from time to time." Even the current Premier of China, Li Keqiang, said that economic data from China should be used "for reference only". This is not a great look, and China is but one of many nations that massages its growth numbers. But how to prove it?

For decades economists have tried to measure other variables that would track GDP when numbers were either suspected to be fraudulent or incomplete. For example, Premier Li said he would look at electricity consumption, rail cargo volume, and bank lending to determine true economic growth. The idea with the first is that if an economy is growing, then electricity consumption should be increasing as factories churn out more goods and consumers use more electricity in their homes. Of course, only local officials will have access to electricity consumption data, so an independent researcher wouldn’t be able to use it.

Recently, economists have come up with a rather clever way to measure electricity consumption and thus measure economic growth: night-time light intensity. Satellites consistently take pictures of the Earth at night - you may have seen the resulting composite image below:

This photo tells you a lot about the world. The eastern half of United States is much more densely populated than the western half . Almost all of the Amazon Rainforest is dark. The Nile River is clear as day. Perhaps most surprising is the difference between North and South Korea, two nations arbitrarily divided and once similar but now on different ends of the wealth spectrum (almost like Communism is a terrible idea or something):

Quantifying the brightness of each country is rather easy; divide the world into pixels and create a formula that indexes the brightness of each pixel. That can then be compared to growth. Economists have found that the correlation is very high; countries that report higher growth consistently have similar growth in light intensity. This technique was originally thought of as a way to measure GDP growth in poor countries that don't have comprehensive data and is accepted by most economists as a valid tool.

Part II: The Paper

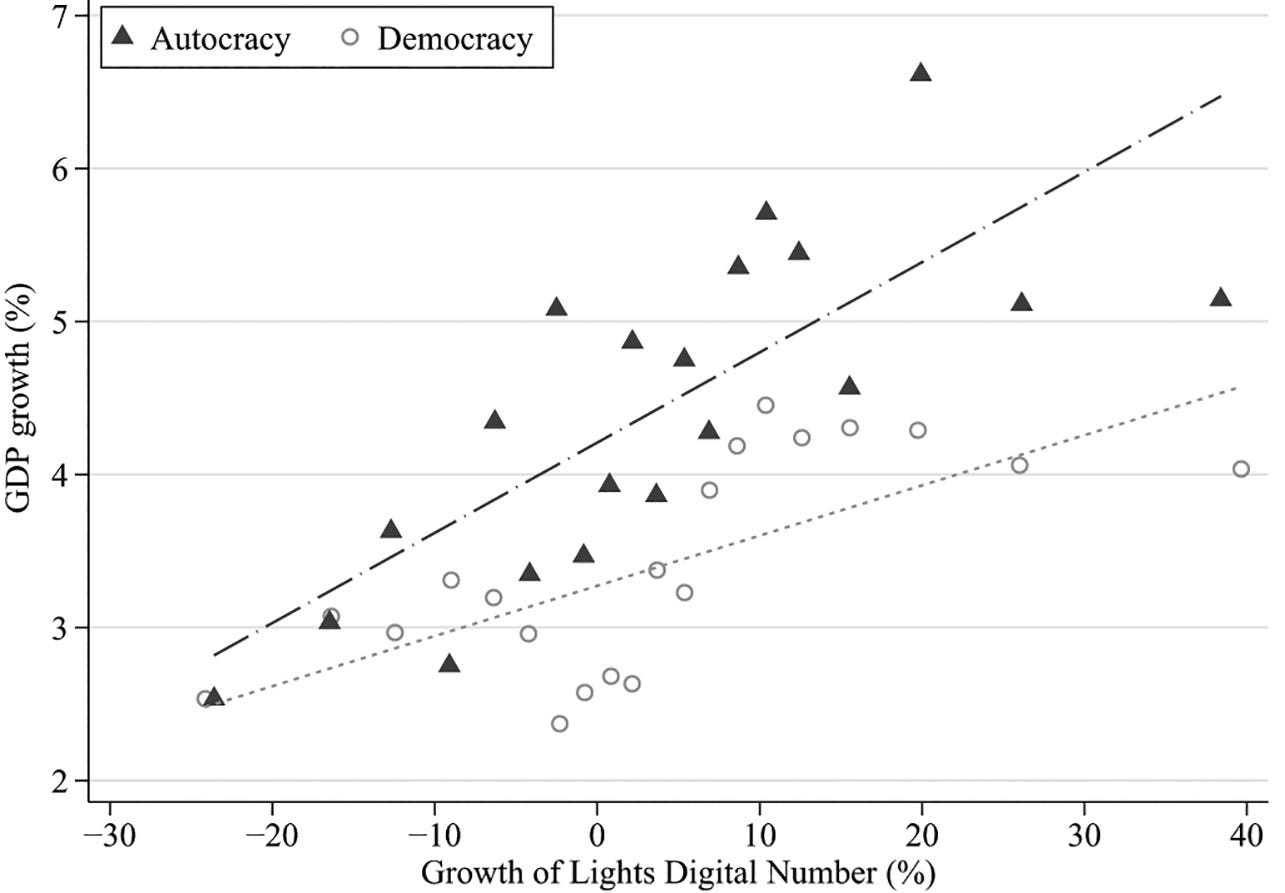

Enter Luis Martinez of the University of Chicago. He asks a great question: can we use night-time light intensity to determine how much authoritarian countries are exaggerating their GDP growth? If authoritarian countries like China are indeed exaggerating their growth, the relationship between night-time light and GDP growth should be different compared to democracies. He ran the numbers, and found that yes, there is a difference. When night-time light increases in authoritarian countries, their GDP increases significantly more than when night-time light increases in democracies. In fact, it increases by 35% more.

Key takeaway: Martinez claims authoritarian countries are exaggerating their growth by an average of 35%. The graph below shows the difference between authoritarian states and democracies. The difference is clear; autocracies appear to grow faster as their night-time light increases compared to democracies.

This is the type of paper that can make a career. To conclusively show that authoritarian countries are putting their thumbs on the scale, and being able to quantify by how much, is a big step forward in the nascent field of forensic economics. Of course the big question remains, is the paper conclusive?

A primary concern in any paper is whether the control group is valid. In this case, do democracies actually produce reliable GDP data? If neither democracies nor autocracies are reliable, then that would make interpreting the results much more uncertain. Martinez makes a convincing argument that democracies do publish accurate GDP data. In a democracy, opposition parties would immediately call foul if it became clear that statistical agencies were exaggerating economic information. Journalists would also love to break such a story. It's highly unlikely that a democracy could keep a lie that involves hundreds of civil servants under wraps for long; there are just too many checks and balances. This happened in Argentina, where eventually the country stopped reporting inflation data because no one believed it. Autocracies do not have this constraint; they can put opposition leaders and those pesky journalists in jail for speaking out. Additionally, even if democracies are exaggerating their growth, this would simply imply that authoritarian states are exaggerating their growth by an additional 35%, not that they are accurately reporting numbers.

Another concern for this paper is whether there are structural differences between democracies and authoritarian states that could affect both night-time light and GDP. Different systems of government are going to push for different economic industries. Some autocracies do not want to have to depend on trade less they are blacklisted by the West, so they encourage self-sufficiency. Many democracies are wealthy, and their economies have a comparative advantage in producing services and importing goods from abroad, so they focus on producing services. In any case, if the economies of authoritarian states systematically differ from those of democracies, then they may also differ in their night-time light emissions. Therefore the difference in the graph above could be due to different economic structures, not fraudulent data.

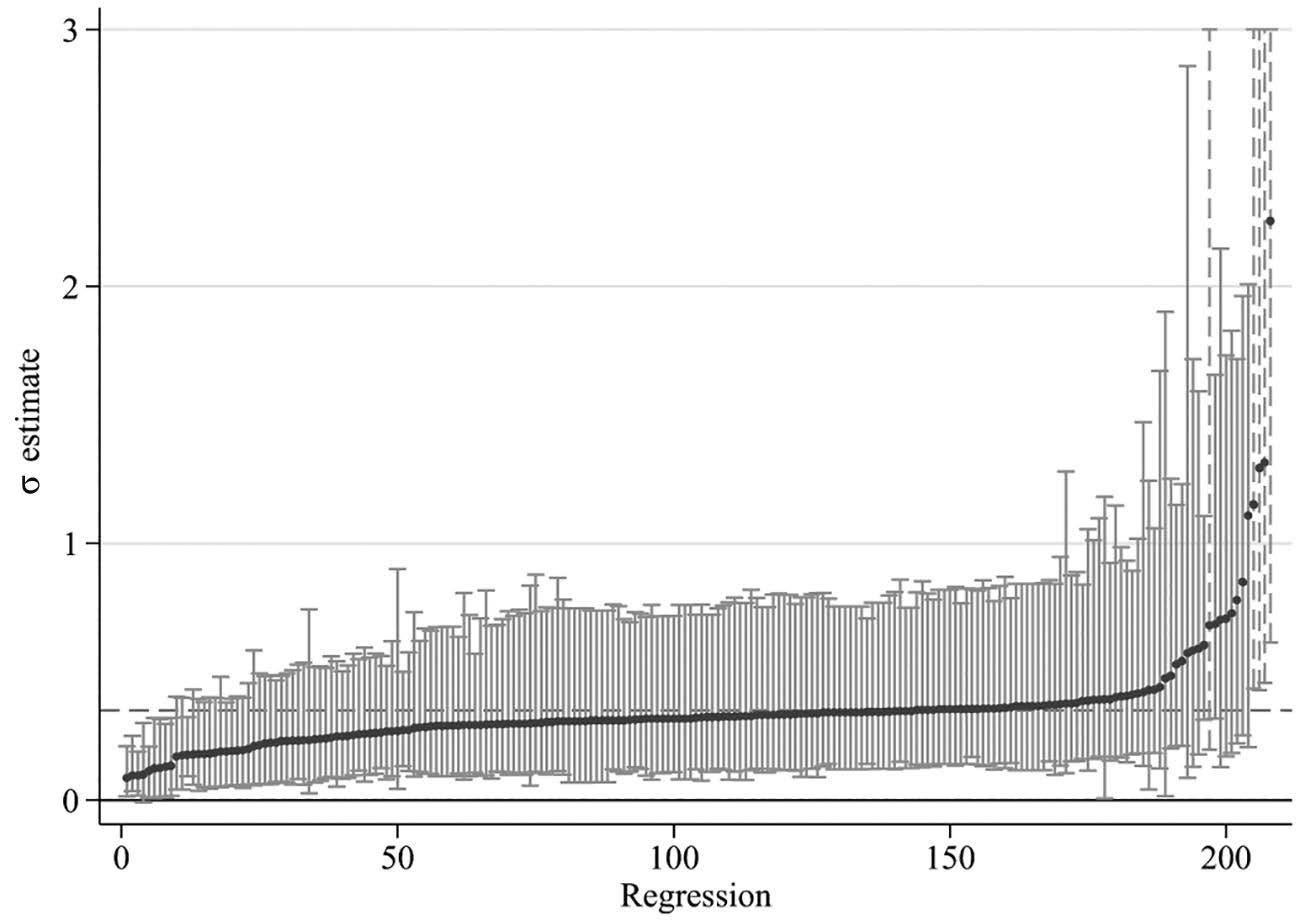

Fortunately, Martinez addresses these concerns and then some. Using standard econometric techniques that are beyond the scope of this article, he tests a myriad of alternative factors. Perhaps authoritarian countries are more likely to have cloud cover at night based on their geography. Perhaps electricity prices are different. Perhaps democracies place more emphasis on streetlights. All of these and more would bias the results and make the conclusion of the paper untrustworthy. Martinez, however, conducts literally hundreds of statistical tests and provides a nice visual summary, reproduced below.

The dotted line is the 35% (0.35) baseline estimate. Each black dot gives an alternative estimate and the vertical bars give the range that each estimate is almost surely within. As the chart shows, the vast majority of tests find that authoritarian countries exaggerate their numbers by around 35%. Almost all show that there is at least some exaggeration going on. Altogether, this figure is very persuasive.

One remaining concern is beyond Martinez's control: it needs a body of literature. This may be one of the best papers of the last year, but is still just that, one paper. To allay all concerns, other economists need to come up with alternative metrics that show similar levels of exaggeration. Eventually, someone will probably challenge Martinez's work formally; it will be interesting to see what his response is. So while this paper is solid, it needs confirmation from other economists. As Scott Alexander succinctly put it, "beware the man of one study". You can always find one study that supports your point of view; knowledge is achieved when a body of literature supports a conclusion.

That aside, how big of deal is this? It's big. China in particular has crowed for years that its system of authoritarianism has outperformed democracies. Other countries have made similar claims. According to official data, not-free countries have a cumulative growth rate of 85%, while free countries have a cumulative growth rate of 61% over the study period. That's a large difference, and providence evidence that having an authoritarian system is preferable from a growth perspective. However, according to the night-time light changes, in reality not-free countries have an average growth of 55% and free countries have a growth of 56%. In other words, if this paper is accurate, the advantage of not-free countries disappears entirely. Given that not-free countries are on average poorer than free countries and due to the catch-up effect poorer countries should have an easier time achieving higher growth, this makes not-free systems look worse than free systems.

Especially concerning China, if this paper is accurate we need to reassess their entire economic system. Based on Martinez's estimates, China's economy may only be half as big as the statistics show! That calls into question their entire economic approach. Again, it will be exciting to see confirmation or refutation of this paper, but for now, it provides a strong argument for democracies over dictatorships.

And I would have gotten away with it if it weren’t for you pesky economists!

- Xi