Red Pen Edit: How Vail Destroyed Skiing

What do you want?

The 2025-2026 ski season has begun! Well, it has if you’re lucky enough to live in Colorado. On October 25, Keystone Resort suddenly announced they would open in an hour and a half to give skiers a few hours on the slopes, and more importantly, beat Arapahoe Basin in the unofficial “first to open” contest. Along with people joyously hitting the slopes, there will undoubtedly be complaints about prices, lines, and Vail Resorts, the largest mountain resort company in the world.

What do people complaining about the state of skiing want? As I wrote about several years ago, it isn’t always clear. The above video echoes a familiar sentiment: that Vail Resorts is destroying skiing. The video is highly watchable and informative, but ultimately, is not well-reasoned. If you have time, watch the full video. If not, some of the video’s claims with my notes are below.

As a business, the ski industry continues to hit new heights. Resorts have seen record numbers of skiers in recent years. Revenue is streaming in.

Call me crazy, but this doesn’t sound like an industry that is being “destroyed”.

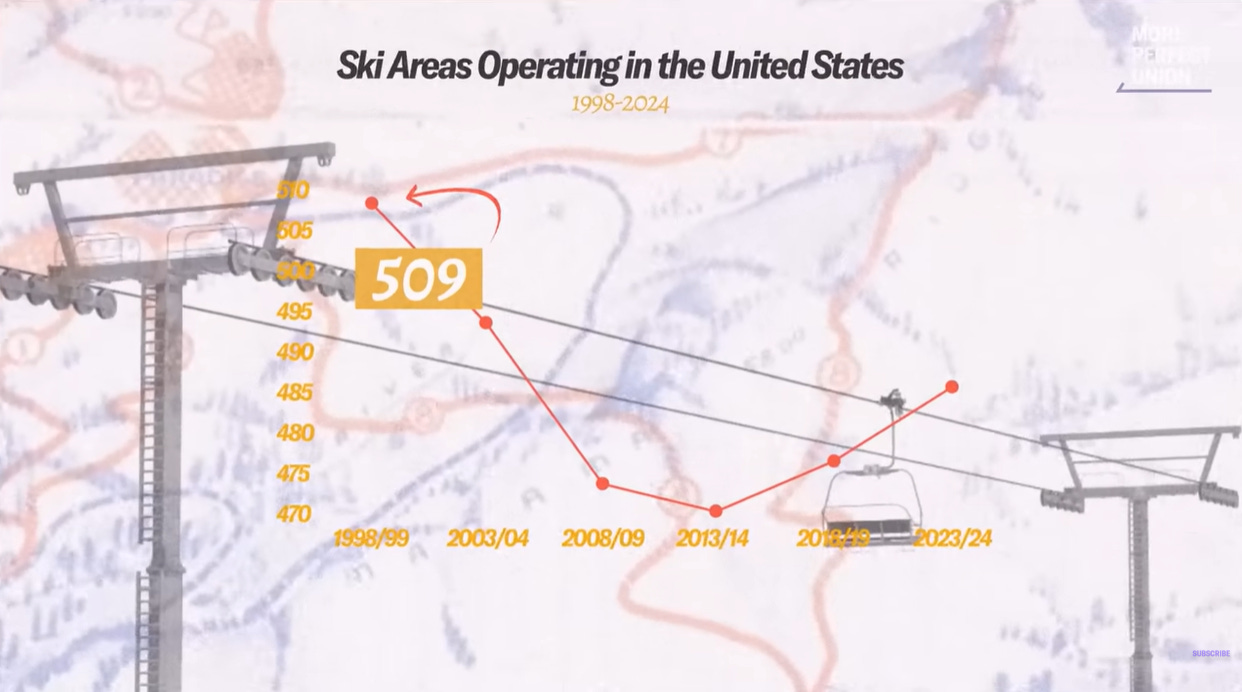

It wasn’t all that long ago that skiing was much more affordable. In 1999, there were 509 ski areas operating in the United States, and many were battling to charge the lowest price for a lift ticket.

Why would that be? Could be it be because skiing wasn’t profitable back then? The above statement is accompanied by this graph:

So yes, skiing was cheaper back then, because there were too many ski areas! They were competing because supply exceeded demand. This is clear from the graph, which shows that almost 40 ski areas closed over 15 years. It’s also important to note that comparing ski prices in 1995 to today is not apples-to-apples. Ski resorts today have better grooming equipment, high speed lifts, more terrain, and most importantly, far better snowmaking equipment. Prices have risen, but the experience is better.

Host: Today, Vail and its rival company, Alterra, own over 50 major ski resorts. and have control of over half of the entire U. S. ski market. They are the most powerful names in the industry, and together, they are simply known as ‘the duopoly.’

This may be the largest industry consolidation that’s occurred in the United States over the last twenty years. An entire industry shifted from mostly local ownership to being part of one of two large corporations. I’ve never heard of such a consolidation happening so quickly.

A duopoly can have advantages and disadvantages. The main advantage is that one large company can increase efficiency through economies of scale. It can raise funds and devote resources that bring down prices. This is why Walmart was able to run most local discount stores out of business. It lowered prices below its competitors, and consumers have benefited. The disadvantage is that without competition, a duopoly can raise prices. This has been well-documented in the airline industry. When airliners merge, prices have gone up. So yes, market consolidation can either benefit or hurt consumers depending on the industry.

Hal Singer, Economist: What independent ownership does is it creates really strong, and I would submit, healthy incentives for the owner to treat its customers and its workers well. But once these firms get rolled up by these kind of faceless private equity firms, it’s really no longer anyone’s responsibility.

Blargh. This is one of those claims that gets repeated so often that it appears to be true by default. First, claims like this need evidence. People love the idea of a locally-owned mountain, but I haven’t seen any objective evidence that a local mountain treats its customers or workers better or worse than a large company. Some probably do. Some probably don’t. It just isn’t true that locally owned businesses universally treat their employees better than large ones. One journalist went undercover and worked at Walmart and found it much better than the media would have you believe. I know I’d rather work at Marriott or Hilton than the local bed and breakfast. Also, “private equity firms” are being used as a boogeyman. Vail Resorts is a publicly traded company!

Host: And in 2008, Vail changed the sport with an all mountain, all access card, the Epic Pass, which gives skiers access to all 40 plus Vail owned resorts for around $1,000. If you buy one thing this year, make it the Epic Pass. In 2018, Altera followed suit with its own pass, the Ikon, offering access to skiing at 17 destinations.

Lou, Ski Employee: Having the huge season pass option that you can go to many different ski resorts sounds like a good idea, but I am not sure that it’s being executed in the best way.

Host: The cutoff to buy a pass this year was at the beginning of December, locking in large payments before any skiing is done. For Vail and Alterra, this was a game changer, creating financial stability in a market that historically had its revenue reliant on unpredictable snowfall.

This is another massive change to the ski industry. There were always season passes, but they were usually very expensive and only for one mountain. Ski resorts had a usage model of revenue: the more people skied more days, the more money they made. The result, as already seen, was that operating a ski resort was risky. As one mountain employee told me at the then-independent Eldora Mountain Resort in Colorado, “You start the season deep in the red, and spend all year trying to dig out. It’s often only the last few weeks of a season that make you profitable.” This is not a good way to run a business. Vail and Alterra have realized that by pushing everyone to season passes, they no longer rely on the whims of Mother Nature. They have a good idea by Thanksgiving what their revenue will be for the year. Previously, two dry winters in a row could bankrupt a long-running ski resort. Now, most people have already bought their passes, booked their flights, and reserved hotels before the resorts have even opened. This allows resorts to invest more money into improving their product, and yes, generate higher profits.

Host: For a lot of hardcore skiers who can visit lots of resorts and ski a lot of days, these passes actually save them cash. The problem is that if you’re just a casual skier or have a whole family that wants to ski, the alternative to those passes isn’t much of an alternative at all. The price of day lift tickets has soared in recent years, and that is a major part of the strategy.

Hal Singer, Economist: The prices of the day tickets and the season passes are interconnected. If you raise the price of the day tickets, it starts to make the season package look affordable. Now, it’s anything but. They’ve gotten the season package up to around $1,000 a year now. But that starts to look affordable because they’re raising the price of what I call the outside option or the standalone daily price into the just say $300 range.

Host: In 2011, a lift ticket at Park City Mountain cost $90. This year it hit $327, a 263% increase.

Ok, this is where I began to doubt the motives of the makers of this video. Watching this, you are led to believe your only two options are to buy a season pass for around $1,000 or spend $300 on a single-day lift ticket bought at the mountain.

This completely omits the existence of Vail’s “Epic Day Pass” and Alterra’s “Ikon Session Pass”. Customers can buy a four-day lift ticket for Vail’s mountains for $463. A four-pack on the Ikon Pass was $489 until prices increased to $569 last week. A single-day ticket from Vail is $128. Now, these have to be bought in advance. You can’t just show up at the mountain anymore and step on the lift for $100. But going from $90 in 2011 to $128 in 2025 sounds… reasonable to me? The increase isn’t notably more than the increase of any other high-priced leisure activity.

Host: If you’re able to swing that upfront price for a pass and manage to visit a ski resort several times a season, the system is a good deal. Unless you’re skiing during peak times. With all those pass holders having access to the same number of mountains, more skiers are showing up to more resorts more often. And in most cases, the ski areas are just not big enough for all of them to enjoy it comfortably.

This is where we get to the fundamental problem with the complaint about skiing. You cannot argue that 1) lift tickets should be cheaper and 2) the mountains should be less crowded. This is an either/or scenario. If you want cheaper lift tickets, the mountains will be more crowded. If you want fewer crowds, then prices have to go up. It’s that simple.

Host: Here in Park City the medium home sale price in December 2024 was $2.9 million despite a 60 percent vacancy rate. Ski towns are experiencing extreme housing shortages as resorts build more and more hotels and apartments and houses are transformed into Airbnbs to accommodate visiting pass holders from out of town. It’s tough for locals and workers alike.

This is a massive problem. It is not the fault of the ski resorts. Ski areas lack housing, as I’ve written about many times, because local governments have made it impossible to build housing. The towns near ski areas are filled with million-dollar, single-family homes. Five-story apartment buildings are rare. If you want to make housing more affordable, you need more housing. Start ripping out bungalows and replace them with apartment complexes.

Host: At the end of 2024, after weeks of failed negotiations and during one of the busiest ski weeks of the year, Lou and his fellow ski patrollers went on strike… The union won the strike, dinging Vail’s stock price and earning big pay raises. Other ski patrol unions at Vail-owned resorts are looking for new contracts, as are unions at resorts owned by Alterra.

Good for them! Just as most private companies should be allowed to charge what they want, most workers should be able to demand higher wages. This was a nice victory for organized labor.

Host: One of the resorts on Indy Pass is Black Mountain in New Hampshire, a beloved local hill that couldn’t keep up with the big operators. So Entabeni bought Black Mountain temporarily, with the intent of turning it into a co-op owned by members.

Again, great! If you don’t like mountains being bought up by the duopoly, turn a mountain into a co-op that will remain with the community. Just don’t be surprised when your supposed loyal fan base disappears during a snowless winter. There’s a reason so many local resorts have closed or sold while the mega resorts are more crowded than ever.

Ultimately, this is a supply and demand issue. If demand exceeds supply, prices will rise and crowds will build. For those unhappy with the status quo, I have a simple, non-rhetorical question: What feasible outcome do you want? I know what you truly want is $50 lift tickets, no lines, and fresh powder up to your knees. So do I. But that isn’t possible. It’s a fantasy.

So what possible outcome do you want? If you want less crowding, then there needs to be higher prices. If you want lower prices, then there are going to be larger crowds. The only possible alternative is to develop large swathes of the Rocky Mountains. I’m all for that. Let’s turn the I-70 corridor into one ski resort after another. This, of course, is going to be met with howls of rage from environmentalists. It will never happen.

If what you really want to do is just complain, fine. Just make sure it’s clear that’s all you’re doing.

The comment section on that vid is a gold mine. You've just gotta sort by newest first.

A comment on the video reminded me: Skinning up is still free! You're just paying for the lift ticket, and there is much excellent backcountry terrain if you don't like the crowds.