The Job Market for Economists

Not what it used to be

I spent most of my college years aspiring to be an English professor. I wanted to specialize in the metaphysical poets of the 17th century. So I did what everyone recommended. I was admitted to the English honors program, took classes with the best professors, began a senior thesis on John Donne, and even founded my university’s poetry club. I knew becoming an English professor was highly competitive, so I wanted to be in the best position possible when applying to graduate school.

As my college semesters went by, I began to have doubts. It became clear to me that becoming an English professor wasn’t difficult; it was nearly impossible. Schools around the country churn out English PhDs by the thousands, but there aren’t that many tenure-track jobs. I also realized that, as much as I enjoy reading and thinking about reading, I didn’t enjoy the way the English discipline writes about literature. In a misguided attempt to become more rigorous, literary theory had become needlessly complicated. Scholars debated the merits of different novels through the lenses of constructionism and deconstructionism and use enough jargon to make an AI programmer blush. I slowly realized that becoming an English professor was not a journey I wanted to attempt.

Fortunately, my parents were wary of the usefulness of an English degree, and they insisted I double major in something a bit more practical. I chose economics, mainly because the major was housed in the same college as English and would make for an easy additional major. I also began to look into getting a PhD in economics instead of English. I never had a road-to-Damascus moment from one discipline to the other. Instead, it was a slow discovery. A few events, however, stand out in my conversion from the decaying temple of English to the one true path of economics. One sociology professor told me it was far better to get a PhD in economics over his own discipline. Steven Levitt, the author of the book “Freakonomics”, gave a fascinating talk at my school. The Great Recession made economics a hot topic.

I also found a few blog posts that extolled the virtues of a PhD in economics. They were upfront about the difficulties, but emphasized how it was relatively easy to get a tenure-track job straight out of graduate school. Most importantly, the backup plan for many econ PhDs, should they fail to make it as an academic, is to make gobs of money in the private sector. I can’t track down any of the old blog posts I read from circa 2010, but the popular 2013 post by Noah Smith titled “If you get a PhD, get an economics PhD” reiterates a lot of what I had read.

Fortunately for me, everything I read proved true. Getting an econ PhD is difficult. It means years of doing advanced mathematics. Trying to find answerable research questions that will publish well. Hunting down data. Having to live in near-poverty for most of your 20s while your friends are taking trips to Cabo. When I graduated in 2016, however, the cheese was still at the end of the maze. I was offered a good tenure-track job right out of my PhD program, despite graduating from a department ranked in the 40s. Almost everyone I knew had a similar outcome, although a few had to take a visiting position for a year or two before securing their own tenure-track job. Noah Smith wrote an update to his 2013 post in 2021, and concluded an econ PhD was still a great bargain.

No one knew the good times were about to end.

After years of a strong econ job market, Covid put the halt on everything. The econ PhD job market follows the academic calendar. Jobs are posted in the fall, first round interviews happen in January, and final interviews and offers are extended throughout the spring semester. The 2020-2021 cycle, known as the 2020 job market, was a bloodbath. Almost no schools were hiring. This makes sense for some institutions, but represents a total lack of vision by many universities. Because most schools didn’t hire during that cycle, it presented a prime opportunity for second-tier universities to snag top talent. A school like Lehigh University, for example, is ranked around 45-50 nationally but has an endowment over $2 billion. It could have easily poached top talent by hiring in most fields. Professors who normally would have gone to schools like UC Davis or Georgia Tech would have settled for what was available. Alas, few schools recognized the opportunity, and the 2020 job market was a nightmare.

The econ market, like many, rebounded in 2021. Hiring was similar to 2019, a useful benchmark because it was an average year. The 2022 job market was also healthy. It looked like the 2020 market was going to be an unusual outlier, and the good times for econ PhDs would continue. Unfortunately, 2022 was the end of the line.

The 2023 and 2024 markets were bad. Not Covid bad, but the first time the econ job market had back-to-back down years in recent memory. This set off a lot of alarm bells. In July of 2025, the New York Times ran an article titled “The Bull Market for Economists Is Over. It’s an Ominous Sign for the Economy.” The article ricocheted around the economics discipline. Why a graduate student would openly advertise he can’t find a job is curious, but the data supported his claim: getting an econ PhD from a decent school was no longer an automatic job.

What happened?

Three things. First, universities reduced hiring in all disciplines. The next decade will not be kind to higher education in the United States. For years, all of academia has discussed the population issue known as the “demographic cliff”. In 2007, as the economy tanked, people stopped having as many children. Many thought it would be short-term and births would bounce back as the economy improved. Instead, it became the beginning of a trend. Not only did birth rates decrease during the Great Recession, they continued to decline. The result will be fewer 18-year-olds and a decrease in demand for college students. On top of that, the Trump administration has put a stranglehold on international admissions. Universities hoped to fill their classrooms with foreign students, but that pipeline has constricted. Less demand means less staffing.

Second, the Trump administration has also decreased the size of the federal government. For many years, a host of federal government agencies would hire dozens of econ PhDs. They worked everywhere from the Department of Agriculture to the Department of Justice. Many of those agencies have at least reduced the number of quantitative specialists they want to employ.

Third, the private sector’s thirst for econ PhDs has finally been quenched. As data became more available in the 1990s and especially 2000s, econ PhDs had seemingly guaranteed employment in corporate America. Companies like Microsoft started an entire research arm that employed many PhDs. Target hovered up anyone with data chops to maximize their profits. Those jobs still exist, but again, industry is not hiring as rapidly as before.

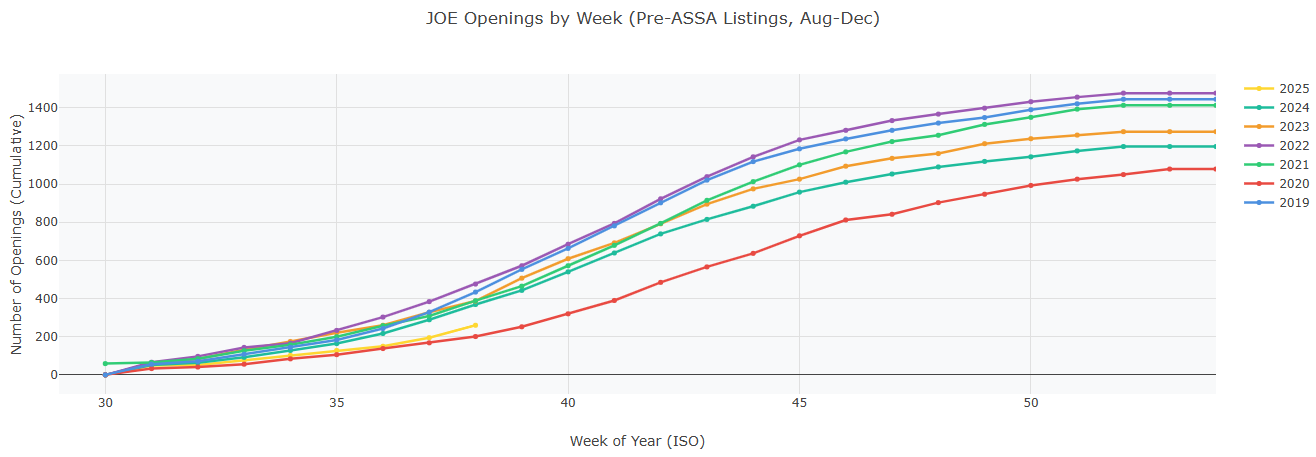

With all three routes of employment narrowing, things aren’t looking good for the dismal science. Relative to other disciplines, the job market for econ PhDs is still good, but it’s no longer the undisputed king of the mountain it was before Covid. Even more disturbing is how the 2025 market is shaping up. It’s early days yet, and most jobs won’t post until later in the fall, but as of the end of September, the market looks rough. Not quite as bad as 2020, but close. Take a look at the jobs that have been posted on the main job board for Econ PhDs:

That red line of despair? That’s 2020. The yellow line of sadness? 2025. The number of jobs available this cycle is closer to 2020 than any other year. That’s not good, especially in the wake of back-to-back below average years. I guess the silver lining is it’s a great time to be hiring. For job seekers, however, the days of a guaranteed job are over.

At least it’s still easier than trying to be an English professor.

I studied economics for its versatility, up to a bachelor’s degree. What stuck with me most was the skill of synthesis, taking bits of information from different places and turning them into a clear story for decisions.

Economics translates complexity into action, and that way of thinking feels more valuable than ever. The job market may be tough now, but I believe the need for people who can connect the dots will only grow.