The Mississippi Miracle

A qualified success

Thank God for Mississippi. It’s a phrase that state officials have used for decades. Why? Because those who live outside the Magnolia State don’t have to worry about being ranked 50th. That’s how bad it is in Mississippi. Whether the statistic is crime, poverty, education, or wealth, you can expect Mississippi to bring up the rear. It has historically ranked 50 out of 50 on many metrics. Thus, state officials in any of the other low-performing states rejoice at the dubious honor of being no worse than 49th.

And Mississippi is not just barely the worst. Especially when looking at GDP per capita, it’s a true laggard. There are nine states that have a real GDP per capita between $45,000-$50,000. That’s low income and shows what the typical low-income state is like. Mississippi, however, is not only the only state to have a real GDP per capita below $45,000. It’s the only state to have a real GDP per capita below $40,000. It is an outlier, and that has helped result in Mississippi come in last place in almost everything.

Until now.

At least with regard to education, Mississippi is going gangbusters. Far from being at the very bottom, especially at the fourth-grade level, Mississippi is now a respectable state. According to the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) test, the state is now often in the middle of the pack. It’s being called “The Mississippi Miracle”. A think tank named the Urban Institute made waves when it declared that after making demographic adjustments Mississippi was the best-performing state in the US. First in fourth-grade math, fourth-grade reading, and eighth-grade math. Third in eighth-grade reading.

How did they do it? By having a multiprong approach. First, accountability. Schools must not pass students who aren’t up to snuff into higher grades. That’s how you wind up with high school graduates who are literally unable to read or write. Standardized tests must be given regularly to track student progress. Students who underperform are held back to repeat grades. Second, teach a curriculum that’s proven to help students learn the material. Mississippi will hopefully be the final nail in the coffin of the “reading wars”, a quixotic quest by some teachers to move away from proven phonics-based instruction, and instead teach students to read by using the whole language method. Why teachers fight to avoid accountability and use discredited reading methods is a rant for a different day, but regardless, Mississippi has shown incredible progress.

There are a few caveats to the good news.

First, while some outlets such as The Free Press are shouting from the rooftops, it’s worth reiterating that the headline-grabbing “Mississippi comes in first” is only after demographic adjustments have been applied to the data. The legitimacy and usefulness of such adjusted data are difficult to determine. On one hand, it makes sense to account for the number of non-English speaking students taking a test. We would naturally expect students who are native English speakers to do better on a reading test than non-English speakers, even if the respective schools are of the same quality. It’s defensible to adjust for income for similar reasons.

There are downsides to this type of adjustment, however. For one, the variables included and not included in any adjustment now make the interpretation of the scores more subjective. What is included and what isn’t? The Urban Institute includes the percentage of students on subsidized lunch programs but does not account for the overall education level of a state. That’s probably a defensible choice, but a choice nonetheless. Additionally, I’m worried that the adjusted variables might be endogenous. A state with poor schools is going to graduate students who don’t have as many skills as employers want. Therefore employers will not hire graduates from those states. Salaries are lower as a result and more students are likely to qualify for subsidized lunches. Thus, accounting for income in current students could be masking a result of bad schooling.

Advocates are also selectively choosing what they adjust for. Much is being made that Mississippi is not only improving, but improving without dumping money into the school system. In terms of thousands of dollars per student, Mississippi is one of the most stingy in the country. However, the comparison needs to be kept consistent. If test scores are being adjusted for income, then spending per pupil needs to be adjusted as well. Connecticut may spend twice as much per student, but its GDP per capita is twice as high as well.

A second caveat is that the best results are for the fourth graders. Especially when looking at unadjusted scores, fourth graders in Mississippi are doing significantly better than eighth-graders in Mississippi. The next few years will tell us if the Mississippi approach is successful in educating students up the entire K-12 chain. In a few years, will eighth graders see the same jumps that fourth graders are seeing today? A few years after that, will SAT scores increase as these students graduate from high school? That will be a true testament to the success of Mississippi methods.

That said, Mississippi is clearly doing something right. I was worried they might be cooking the books by flunking out poor students, so it was heartening to hear one expert say, “It’s not that they changed their test some year or played some game that made their scores look better. We’ve seen a lot of that kind of thing, and I’ve learned to be super-skeptical. When you get these kinds of gains over this period of time, something real must be going on.”

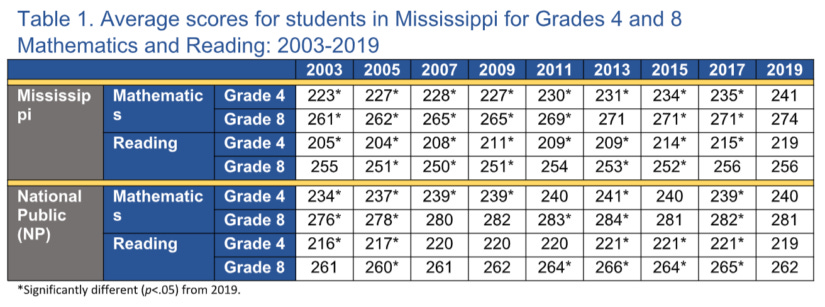

On top of that, the raw numbers show significant improvement:

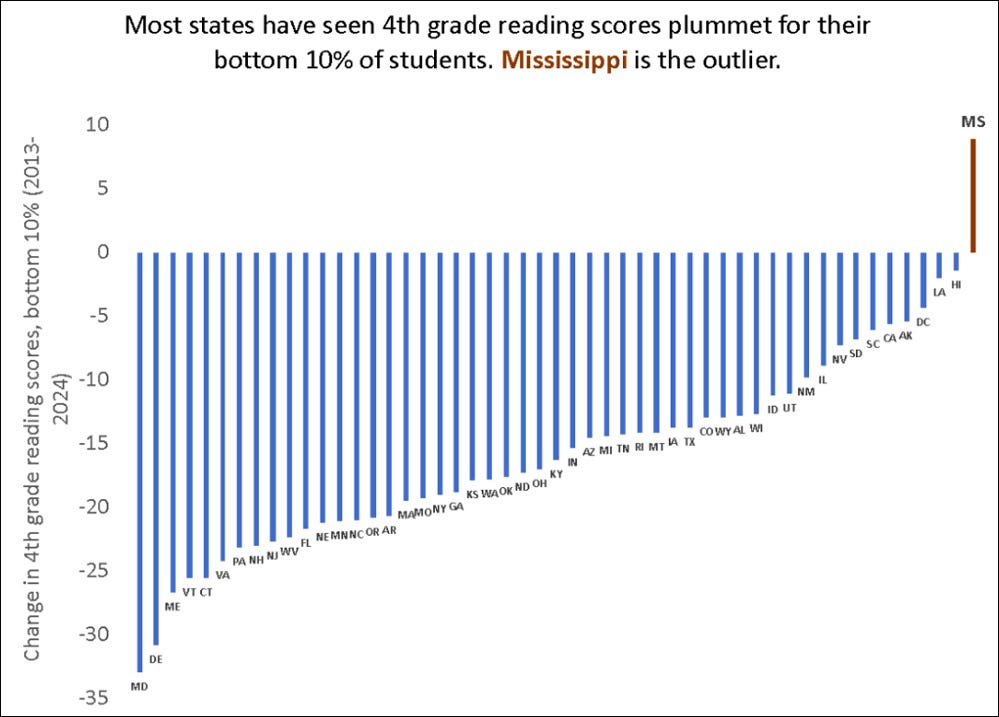

With the exception of eighth-grade reading, the improvements in Mississippi are significantly larger than the nation at large. Even more impressive, students at the bottom of the distribution have declined in performance in every other state, but in Mississippi they have improved:

So while some of the headlines out there are a bit overblown, Mississippi has shown that real improvements can be made. They have put in years of effort, increasing accountability and solid curriculum design. Their students have shown improvement, with some of the largest gains coming from the bottom. The day may soon come when state officials say, “Thank God for Mississippi” not in jest, but because Mississippi had shown them a path towards better schools.