Economics for Muggles: The Columbine Shooting and Housing Prices

Using a natural experiment to quantify stigma

This is the second installation of my Economics for Muggles series, where I explain interesting economic papers to non-economists. Find the first one here. In this post I’ll be addressing one of the first academic papers I published, which is titled “Social stigma and asset value”

Part I: Background

Would you move into a murder house? That is, would you be willing to move into a house that someone was murdered in, even if you thought there was no risk to yourself or your family? This is the question I sought to answer a decade ago. The idea of paying more or less for a house because of something that happened there always intrigued me. For example, would you pay more for a house that George Washington slept in? On the flip side, would you want a discount to live in a house once occupied by Ted Kaczynski?

Paying less for a house because something distasteful once happened there is an important manifestation of stigma. Stigma is a wily word and tough to define. It can be thought of as an innate distaste for a person, place, or thing. Psychologists have found stigma in various places, often involving disease or pathogens. I wanted to show that the presence of stigma in a property would result in a decrease in home value. The most obvious case of stigma in a house would be one that someone was murdered in. The immediate problem with this approach was it was going to be time consuming to assemble a dataset with enough murder houses to quantify the impact. Newspapers generally don’t publish the exact address of a murder, and realtors will do their best to hide the connection of a murder to a property. One expert estimates that a murder reduces a house’s value by 10%-15%, but this is not a rigorous assessment.

So compiling a list of murder houses and comparing them to other houses nearby was going to be, at best, very time consuming. Most likely it would be impossible. I needed another route to look at stigma and house prices. An additional complication is that stigma is hard to isolate. Most negative events that would affect stigma would also have a physical impact. A home-buyer might not want to live in a home that had multiple residents die after a hurricane hit, but along with possible stigma the home would also have suffered severe physical damage. I needed a negative event that would plausibly stigmatize an area, but wouldn’t cause obvious damage to the property. Then I thought of the 1999 Columbine Shooting.

The Columbine Shooting was one of the biggest news events of the 1990s. At that time school shootings were relatively rare, only several had occurred in the United States over the previous 10 years. Columbine, unfortunately, set off a trend of school shootings that continues to this day. Other school shooters have since referred to “pulling a Columbine” and looked at the perpetrators of the Columbine Shooting for inspiration. The event also represented a massive failure of the media, which sensationalized and inaccurately reported details of the shooting for months. David Cullen’s excellent book, Columbine, goes into detail for those that are interested. Every American knew about Columbine. Every American was talking about Columbine. If there was going to be an event that stigmatized an area, this was going to be it.

Part II: The Paper

This paper used what’s called a natural experiment, or a real-world event that happens randomly and allows a researcher to find cause and effect. The idea is straightforward: compare prices of homes that sold in the Columbine area to those that sold nearby before and after the shooting. I did this using two econometric techniques, difference-in-differences and synthetic control.

For these techniques to work, several conditions have to be met. First, the treatment group (houses that feed into Columbine High School) needs to be similar to the control group (houses that feed into other high schools). If Columbine High School was in a super wealthy area or had different demographic characteristics than neighboring areas then there won’t be a good control group. Fortunately, it was relatively easy to show that the houses that feed into Columbine are similar to those that attend other high schools in the same school district. Columbine High School is in the middle of the amorphous western Denver suburbs. There are large residential neighborhoods that were built during the mid-to-late 20th century, with some of these neighborhoods attending Columbine and other neighborhoods attending other schools. This screenshot from Google Maps is useful:

The red line demarcates the boundary between Columbine and other schools; it is clear that the neighborhoods on either side of the boundary are similar.

A second condition is to support the claim that any differences in housing prices must be the result of stigma alone, as opposed to stigma acting in conjunction with several effects. If people fear a second shooting or think that the quality of schooling at Columbine has dropped, then there is more than just stigma. I made the argument that Columbine High School reopened in August 1999 as planned and that Columbine’s school quality remained unchanged as staff members took a strong “return to normal” approach. Also, the media coverage largely referred to Columbine as a one-off event. Even Bill Clinton referred to how “if it could happen in [Columbine]”, referring to the randomness of the tragedy. Thus, only stigma could be affecting housing prices.

So if you buy that the Columbine Shooting was a random event that didn’t leave any noticeable changes to the area and that houses that attend Columbine are similar to those nearby, then any difference in housing prices can be attributed to stigma.

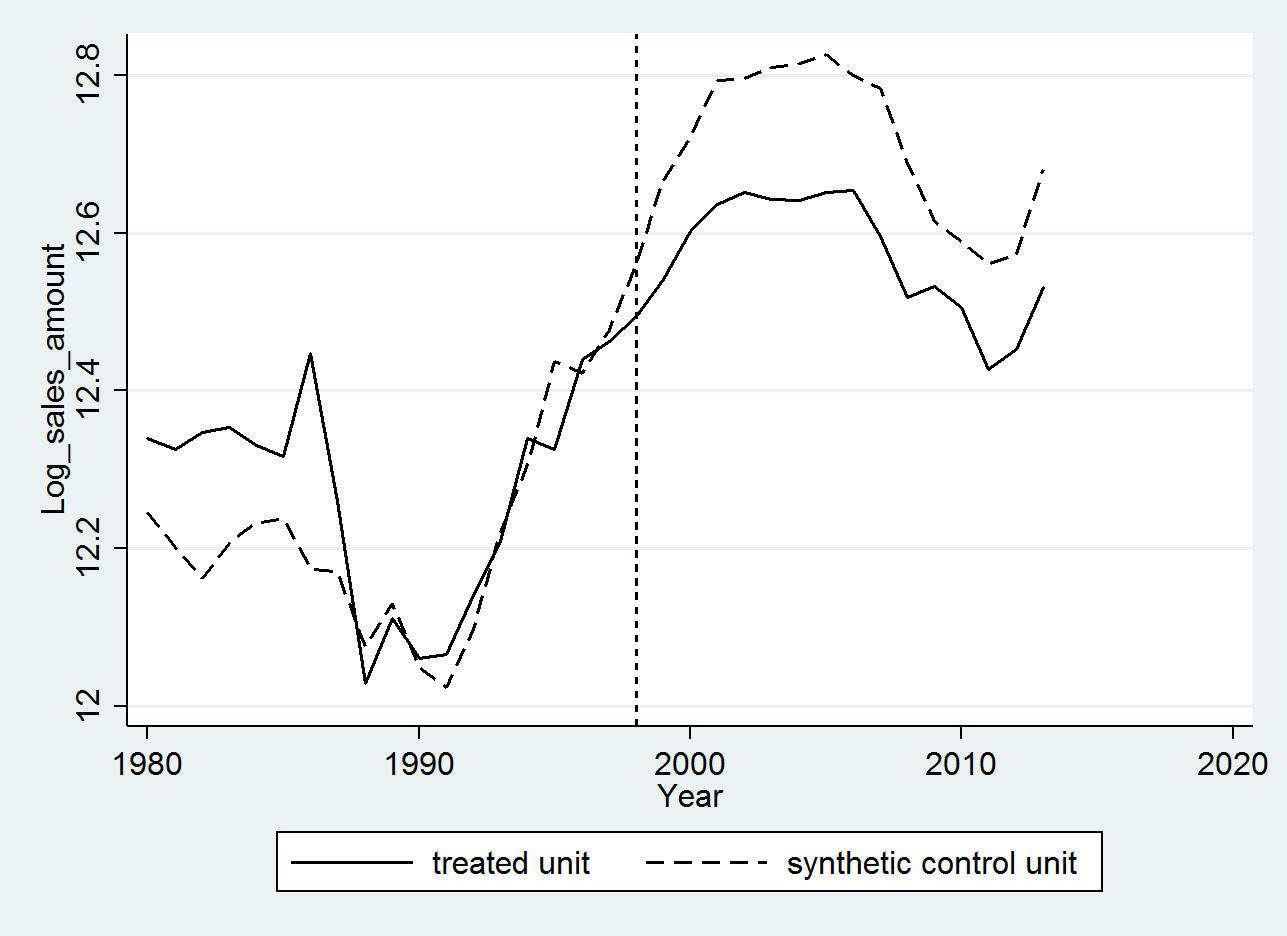

Then it was time to run the numbers. Here is the key graph:

The solid line is the Columbine area, the dotted line the control group. As you can see, in the decade before the 1999 Columbine Shooting, the treatment group and control group are in lockstep with one another. Then, they diverge right about the time the shooting occurred.

Note, and this is key, that prices in the Columbine area did not drop because of the shooting. They just didn’t increase as fast as the control group. This is one of the difficult aspects of economics - finding cause and effect often means identifying a difference in trends between a treatment and control group, not discovering a total reversal in the treatment group identifiable in a vacuum.

So how big was this result? Well according to the analysis, I found that the Columbine Shooting lowered housing prices by about 6% the year after the shooting. So people were still willing to buy houses in the Columbine area, but they needed a small discount on the price. What do you think? Would you buy a house in an area that just had a mass shooting? If so, how big of discount on the price of the house would you want?