Publishing in Economics

A revisit of the Luis Martinez Night-time Light and GDP Article

In January I published my first article in the “Economics for Muggles” series, which discussed Luis Martinez’s 2022 paper (hereafter Martinez (2022)) that found authoritarian countries were likely exaggerating their GDP numbers. This was based on the fact that autocracies report significantly higher growth than democracies even when they have the same growth in night-time light emissions. Read the previous Substack post here. and the academic paper here.

On one hand this paper gives me hope. As I mentioned in the previous post Martinez (2022) is a fantastic article. It makes a convincing case that the growth seen in many autocracies may be overstated. This is an important development in the study of growth and the relative strengths of autocracies and democracies. It’s also an easy to understand paper, that both economists and non-economists can appreciate. This is the type of paper that makes me love economics.

I’m jealous of the author; the approach is relatively straightforward and easy to do. It was published in one of the “Top 5” econ journals, the Journal of Political Economy, an outlet I have never even submitted to. Getting just one hit in a Top 5 journal means you are well on your way to tenure at most colleges (unfortunately for Martinez, who is at the University of Chicago, he’s going to need several more to even be considered for tenure).

On the other hand, this paper makes me despair. Martinez first published a working paper version in December 2017. It wasn’t accepted for publication until August 2022. The amount of time and effort that had to go into this relatively straightforward paper is, to put it bluntly, staggering. I don't know how long Martinez was working on the project before he published the working paper version in 2017, but based on the thoroughness of it, I’d conservatively put it at a year. That means the paper took at least five and a half years to complete. It took around four years to be accepted by a journal after first submission (based on the updated working paper date of July 2018). And while the paper is solo-authored, Martinez had help - not one but two research assistants!

So while this paper is great, it also shows how difficult publishing in the field of economics has become. Even a paper that is straightforward and simple is a massive time commitment by a very talented economist at one of the best universities in the world. And while the published version of the paper is only 39 pages long, that is far from being the entire paper. In numerous places Martinez directs the reader to an appendix, which clocks in at 63 pages. So in reality the final version of the paper is just over 100 pages long. What’s in the appendices? An incredible amount of additional statistical checks, many of which were likely demanded by reviewers during the review process.

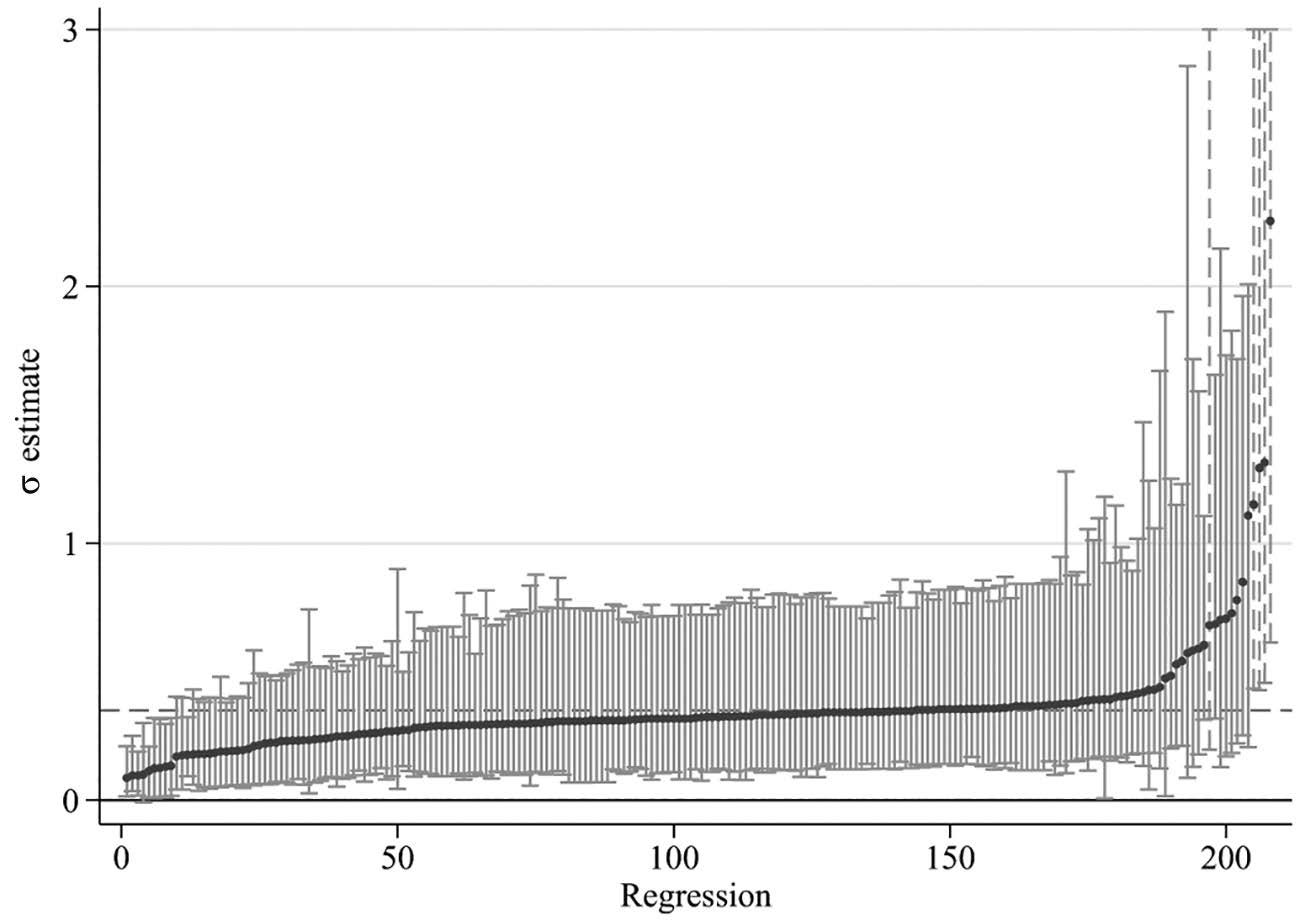

No one like’s having to deal with reviewers. But they are an integral part of the publication process, and everyone recognizes them as fundamental to peer-reveiwed scholarship. That said, in the field of economics reviewers have gotten out of control. The demands they make on authors often approach absurdity. I love the figure that Martinez provides that shows 200 different specifications and how they compare to his baseline 0.35 estimate (the black dots are the mean value for each specification and the dotted line is the 0.35 main estimate):

But that is a ludicrous number of tests! This is why papers take so long to publish. Reviewers at even middling journals want to see test after test after test. They want no rock left uncovered. The result, especially at the top journals, is that it has become virtually impossible for anyone not at a top school to break in. If it takes a top scholar with two research assistants at a world-renowned institution four years to publish, then it effectively ices out most mere mortals. Consider just the teaching constraints of faculty at regional universities. They usually teach two to four courses every semester. Professors at the top teach one to two courses every year. There just aren’t enough hours in the day for most professors to devote this much work to a single project.

Now to be fair to the reviewers of this paper, it makes some important claims. Declaring that autocracies such as China are not as successful as they say they are needs support. This paper was going to attract attention; the reviewers need to be fairly assured of the results. They were right to go voice concerns and ask for additional robustness checks. But 200? An appendix twice as long as the paper? Twenty years ago, before endless appendices could be placed online, this was not that standard. It’s making economics worse off and making it impossible for most researchers to publish seminal work.

The ultimate irony with regard to this paper is that the effect is visible in the raw data. Just plotting the relationship between GDP growth and night-time lights in a simple graph shows the following:

According to Martinez, the difference between autocracies and democracies on this graph corresponds to a 25% gap. That means even before the econometric model, before the regression analysis, before the literal hundreds of robustness checks, the main result could be seen with the naked eye. Now correlation does not prove causation, so the above graph needs much more support before such a claim can be published. That said, after all that work, Martinez concludes the magnitude is 35%, not 25%. Economics, of all disciplines, should recognize the diminishing marginal returns.